Alexandria: Unravelling the Loss of the Greatest Knowledge

Melkisedek Raffles – UKI

For centuries, the Library of Alexandria stood as the beating heart of ancient knowledge — a place where astronomers mapped the skies, mathematicians reshaped logic, physicians experimented with early surgical tools, and philosophers debated the nature of existence itself. More than a library, it was the largest research institute of the ancient world, home to scholars across Greece, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and beyond. Its vast collection of scrolls, laboratories, lecture halls, and observatories made it the cradle of scientific thought. Yet its destruction remains one of history’s greatest intellectual tragedies, leaving behind fragments, legends, and questions that continue to haunt scholars today.

The Golden Age of Alexandria

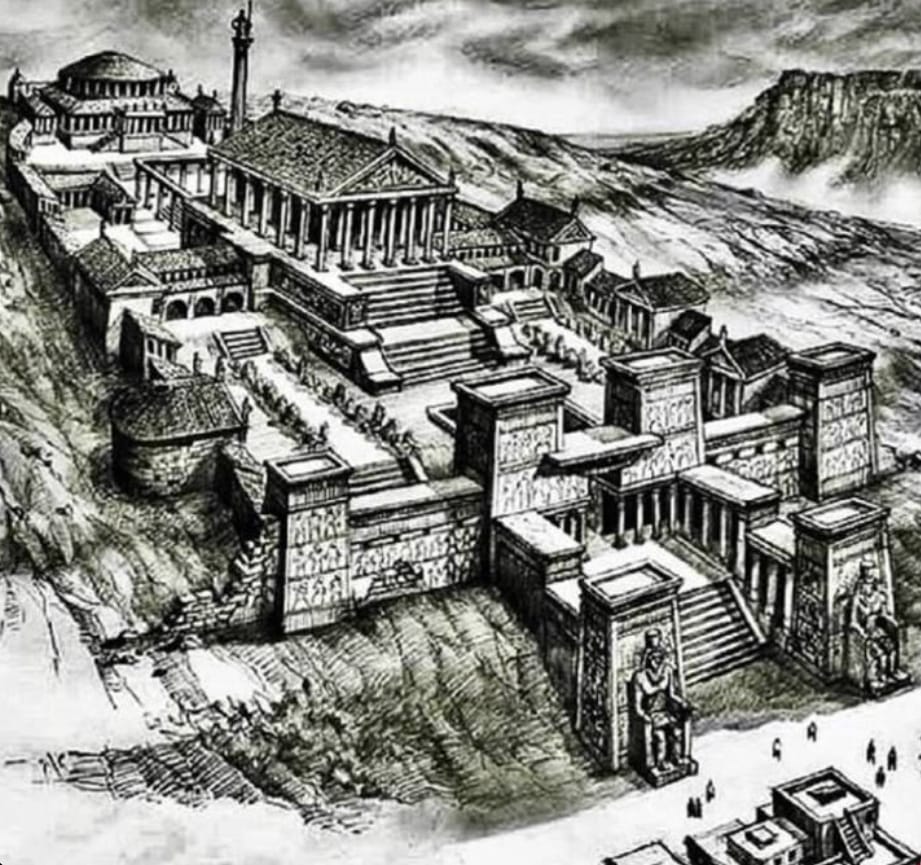

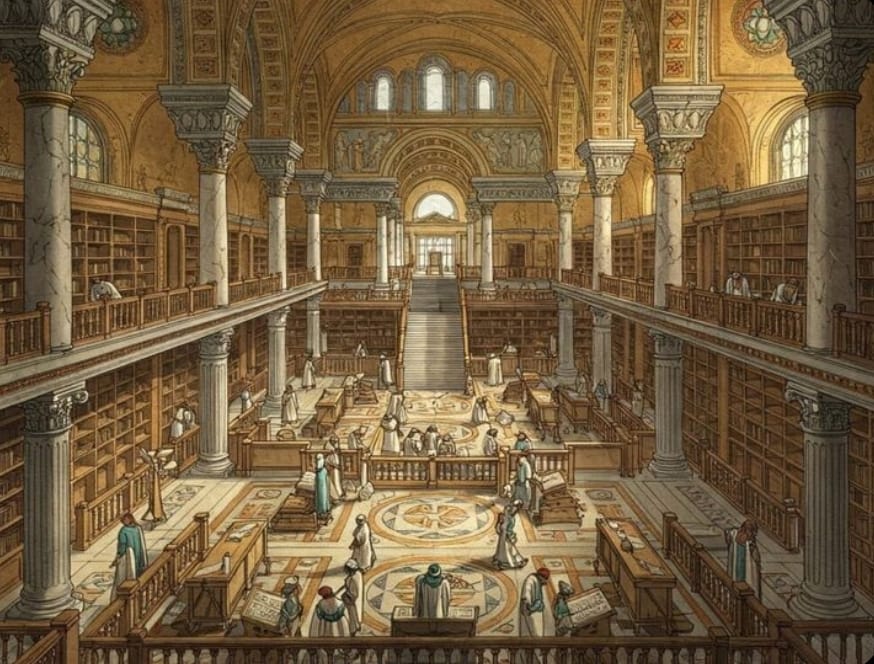

The Library of Alexandria was only one part of a larger academic complex known as the Mouseion, a state-funded institution similar to a modern university. Scholars who lived and worked there were paid by the state, given housing, meals, and access to tens of thousands of scrolls. The library’s interior was divided into specialized rooms: reading halls, cataloguing rooms, translation chambers, botanical and medical rooms, and vast storage vaults lined with shelves of scrolls made from Egyptian papyrus. These scrolls covered subjects ranging from geometry and astronomy to medicine, linguistics, and engineering.

At its height, the Library may have held 400,000–700,000 scrolls, making it the single largest archive of knowledge in the ancient Mediterranean. It was here that Eratosthenes calculated the circumference of the Earth with astonishing accuracy, Euclid wrote The Elements, and Herophilus advanced anatomy and early surgical practice. The Library also maintained the world’s most organized catalog system, compiled by Callimachus, who created the Pinakes, the first known library catalog in history.

Theories Behind Its Destruction

The fall of the Library was not a single event but a long process that unfolded across centuries. One theory places the earliest major destruction during Julius Caesar’s Alexandrian campaign in 48 BCE. Ancient writers claim Caesar ordered the burning of enemy ships, and the flames spread to the warehouses storing scrolls destined for the Library. Modern historians debate the scale of this damage, but most agree that the Library survived in diminished form afterward, continuing to operate under Roman rule.

A second theory suggests its destruction accelerated due to religious and political conflicts. In 391 CE, the Christian Patriarch Theophilus ordered the demolition of pagan temples, leading to the destruction of the Serapeum, a secondary library that housed thousands of scrolls. Another tradition that widely doubted by scholars claims that the library was burned again under the Muslim conquest of 642 CE, though evidence for this is extremely thin. Instead, historians believe the Library gradually declined due to budget cuts, wars, theological conflicts, and loss of scholarly support rather than one single catastrophic fire.

Scientific Instruments, Star Maps, and the Legacy of the Scrolls

Beyond literary works, the Library stored scientific scrolls and instruments used by astronomers and mathematicians. Among these were early astrolabes, celestial globes, and star catalogues that mapped constellations and planetary motions. While none of these original star maps survived, their descriptions appear in surviving works of later scholars. Many historians believe that ideas from the Library influenced astronomical texts that later inspired Islamic Golden Age astronomers and, eventually, European Renaissance thinkers.

The Library is also thought to have housed early surgical tools, as described in medical scrolls by Herophilus and Erasistratus. Some designs reappeared in medieval Islamic medical manuscripts more than 1,000 years later, suggesting knowledge from Alexandria was not entirely lost but reinvented or preserved indirectly through copied scrolls carried out by scholars before its decline.

Hypatia: The Last Light of Alexandria

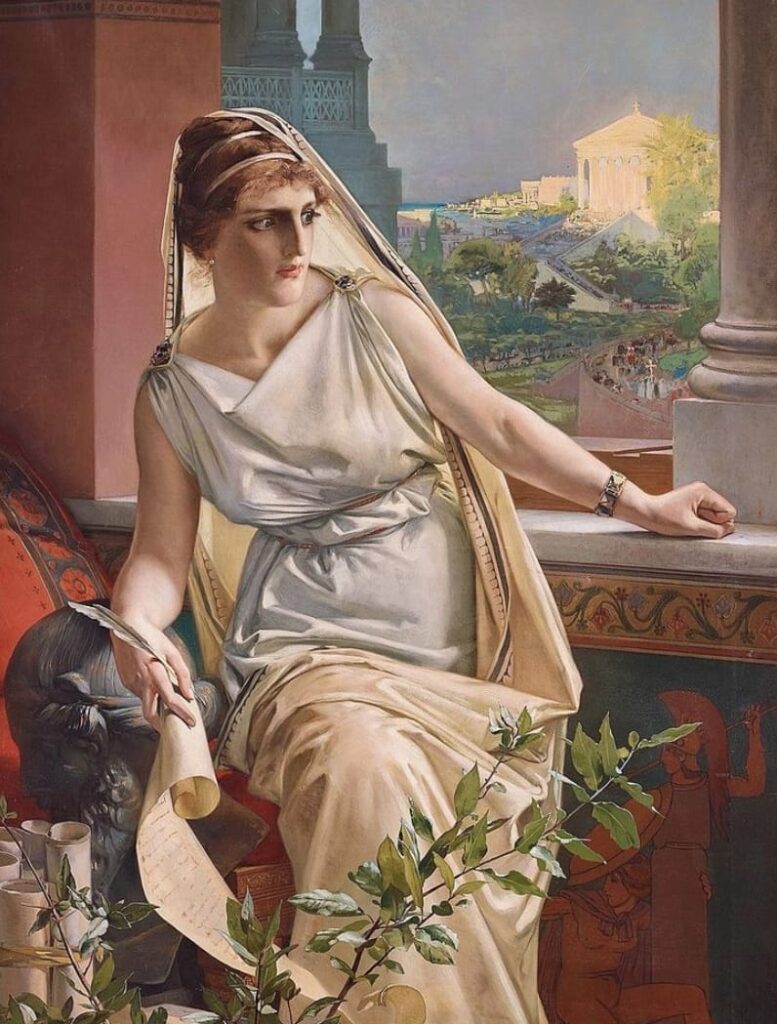

Hypatia (c. 355–415 CE) is one of the most remarkable figures connected to the Library’s intellectual tradition. She was the daughter of Theon of Alexandria, a renowned mathematician and editor of classical texts. From a young age, Hypatia was trained not only in mathematics and astronomy but also in rhetoric, logic, and philosophical debate — skills that turned her into a celebrated lecturer in the revived Museum of Alexandria, which functioned like an elite university.

She taught mathematics, Platonic philosophy, and astronomy to students from across the Mediterranean from Greece and Rome to Syria and Cyrene. Hypatia’s classes did not simply focus on formulas or memorization; she taught her students how to think. She encouraged independent reasoning, skepticism, and intellectual courage during a time when free thought was increasingly dangerous due to rising religious tensions.

Her popularity among Alexandria’s elite and her influence as an advisor to Orestes (the Roman prefect) created political conflict with Bishop Cyril. In 415 CE, she was murdered by a mob of Christian zealots — dragged from her chariot, beaten, and dismembered. Her death symbolized the final collapse of Alexandria’s classical intellectual world.

Contrary to belief, Hypatia lived long after Aristotle (d. 322 BCE). They were not contemporaries, nor was Aristotle her teacher; however, Hypatia preserved his ideas by teaching and editing Aristotelian philosophy. Many of her students secretly preserved scrolls — mathematical treatises, astronomical notes, and philosophical commentaries — which later influenced medieval scholars and eventually resurfaced in works read by figures like Galileo and Kepler. While not a direct chain of mentorship, Hypatia’s intellectual legacy helped keep ancient Greek reasoning alive.

The Dark Ages and the Aftermath of a Lost Library

Although the Library itself vanished, its intellectual DNA survived through scattered manuscripts carried to Constantinople, Baghdad, and Antioch. When Western Europe fell into political chaos during the early medieval period—often called the Dark Ages—Alexandrian knowledge continued to live in the Eastern Roman Empire and later the Islamic Golden Age. Without this preservation, much of Aristotle, Euclid, Galen, and Ptolemy would never have reached Renaissance Europe.

The Library’s fall is often symbolically linked to the beginning of intellectual decline in the West. While “Dark Ages” is an oversimplification, it is true that Europe experienced a significant drop in scientific literacy, literacy rates, and technological innovation. Alexandria’s destruction—spread over centuries—contributed to this loss of continuity.

Yet, the ideas born in its halls eventually resurfaced. During the Islamic Golden Age (8th–12th century), scholars translated surviving Alexandrian scrolls into Arabic, studied them, expanded them, and passed them to medieval Europe. The Renaissance thinkers—Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler—were profoundly influenced by the intellectual heritage that originated in Alexandria.

In this sense, the Library’s spirit survived far beyond its walls. Its collapse may have plunged parts of the world into intellectual darkness, but its preserved manuscripts later reignited global knowledge.

The Library of Alexandria may no longer stand, but its legacy echoes in every scientific and philosophical tradition that followed. Its vast scrolls, revolutionary thinkers, and the brilliance of scholars like Hypatia shaped the foundations of Western and Middle Eastern intellectual history. The Library’s fall reminds us of how fragile knowledge can be and how essential it is to protect the pursuit of truth from politics, war, and dogma.

Preserving knowledge is not only about saving books; it is about safeguarding curiosity, free inquiry, and the courage to think for ourselves values that the Library of Alexandria championed at the dawn of civilization.

*****

Dapatkan informasi mengenai kesehatan mental, edukasi seksual, dan tips pelajar hanya di Majalah Sunday, teman curhat remaja Indonesia.